|

The Vat House.

The chests, huge round vessels, stand in bricked arches, above the level of the vats, to the right of the vatman. To keep the pulp stirred in the chests agitators are used and the driving gear for these is under the bricked arches. It is from these chests that the pulp needed by the vatman to make the paper flows.

The vat is a large square box filled with pulped rags, mixed with water, and heated by steam from within.

Some of the finest papers need a high temperature, this has an effect on the vatman's hands and for this reason, he has by the side of the vat, a hand box of cold water to refresh his fingers.

Inside the vat is a toothed roller known as the hog, this keeps the heavy pulp moving and mixed and prevents any settlement of the fibres. The only utensil used is the mould, the vatman always has two. This is a flat rectangular sieve, of very fine copper wire with the water-mark let in. The sides of the sieve are detachable, these are known as the deckle. The moulds vary in size of two open sheets of notepaper to large squares of double elephant.

To start the making of paper the vatman stands in front of the vat, leans forward, dips his mould into the end of the vat farthest away from him, bringing it gently forward and taking up more pulp in the mould than he really needs, by shaking he makes a little wave over the mould. When this

wave gets to the edge of the mould he makes it run off, leaving just the right amount of pulp to get the required thickness. The mould is then shaken again so that the fibres are spread and interlocked to make a perfect sheet.

This shake of the vatman's arm produces the dovetailing of the fibres which no machine can produce. For a vatman to lose his shake is a tragedy because only on very rare occasions does it ever return.

|

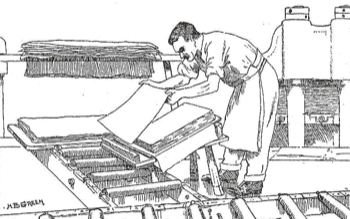

Having made the sheet, the mould is passed, without the deckle, along the stay to the asp where it drains. Putting the deckle on to the next mould the vatman is ready to make his next sheet.

Taking the full mould from the asp the coucher gently presses it on to a felt and covers the pulp with another felt, sometimes needing the help of a felt boy.

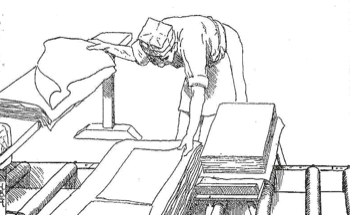

Running the mould along the bridge, for the vatman to pick up, the coucher takes his next mould from the asp. He continues like this, alternate sheet and felt, until a post or lump is ready for pressing.

When the post is taken out of the press it is now solid enough to handle so it starts its journey of two or three months through the mill.

When the post is taken out of the press the layer takes the sheets from between the felts, throwing the felts on to a board, ready for the coucher to use again. The layer puts down two posts, this makes a pack.

Loaded on to trucks, the packs are taken by lift up to the Press Room. Here the dryworker gathers together as many men as he can muster to bear on the levers of the hand presses, to squeeze out, under tremendous pressure, gallons more water. For the last turn a large pole is inserted in the press, and all hands heave with united effort for the final squeeze. Under such pressure the grain mark imparted to each sheet by the felts in the vat house, at the first pressing is removed. When the packs are removed from the presses, after several hours, they go into the dryer.

|